Melvin Sokolsky was one of the greatest pioneers in the creation of visual imagery of all time. Admired, awarded, and relentlessly copied, he remained steadfastly ahead of the curve and thoroughly ignited, even in his senior years, bursting with creative energy, opinion and fascinating anecdotes.

Slowly sipping his cappuccino, Sokolsky is in passionate recollective mode. “My father would bring home a lot of printed matter and it really fascinated me. We’d also go to Central Park often and we’d pass by Rizzoli’s (then on 5th Avenue) on the way. One day I saw this book by Hieronymous Bosch which totally intrigued me and my father asked me if I wanted it. My parents always gave me the message that they would allow me to do what I wanted to do, because they trusted me. My father bought me the book and I kept looking at Bosch’s paintings, in particular ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’, in which there is a couple in a bubble. That image has stayed with me since my childhood.”

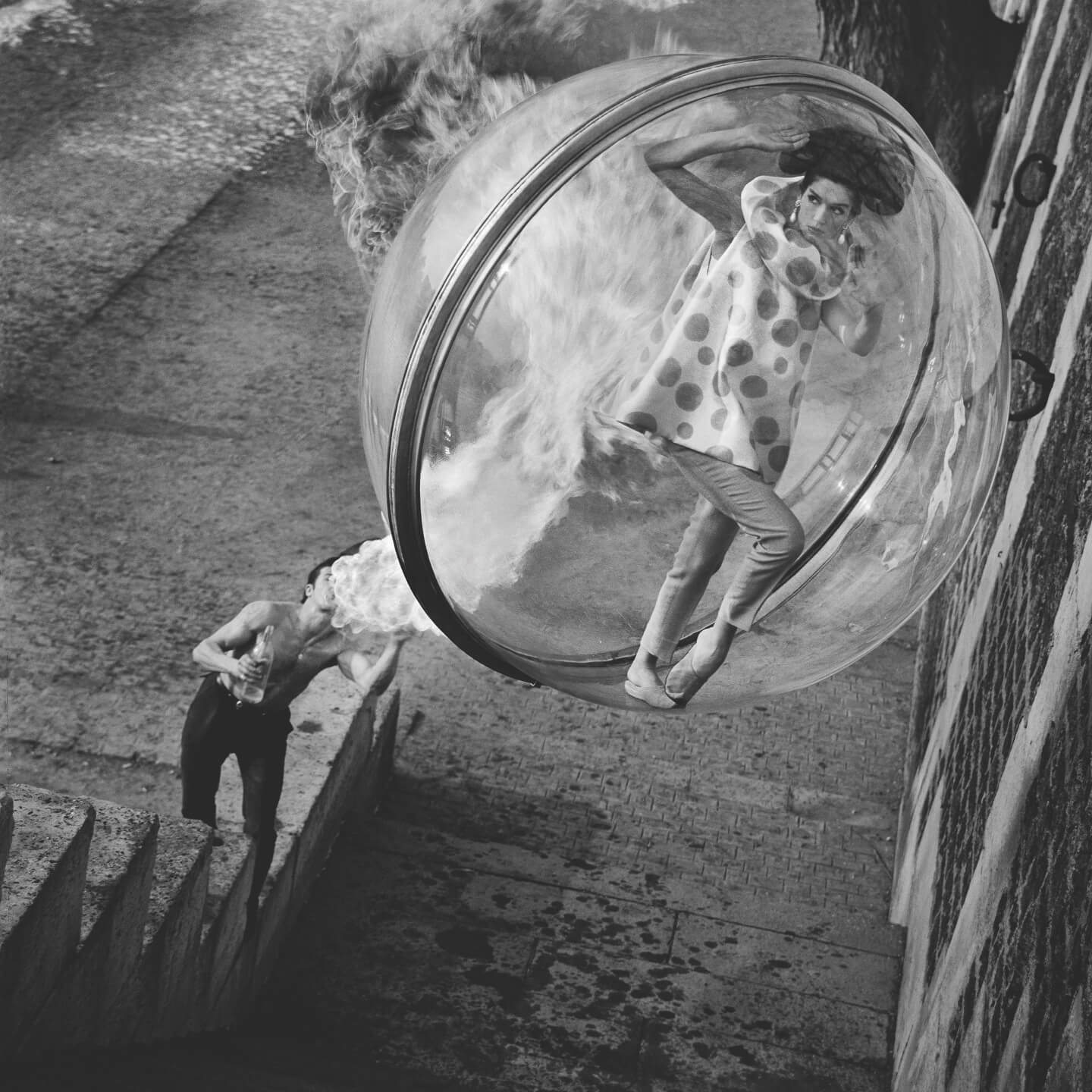

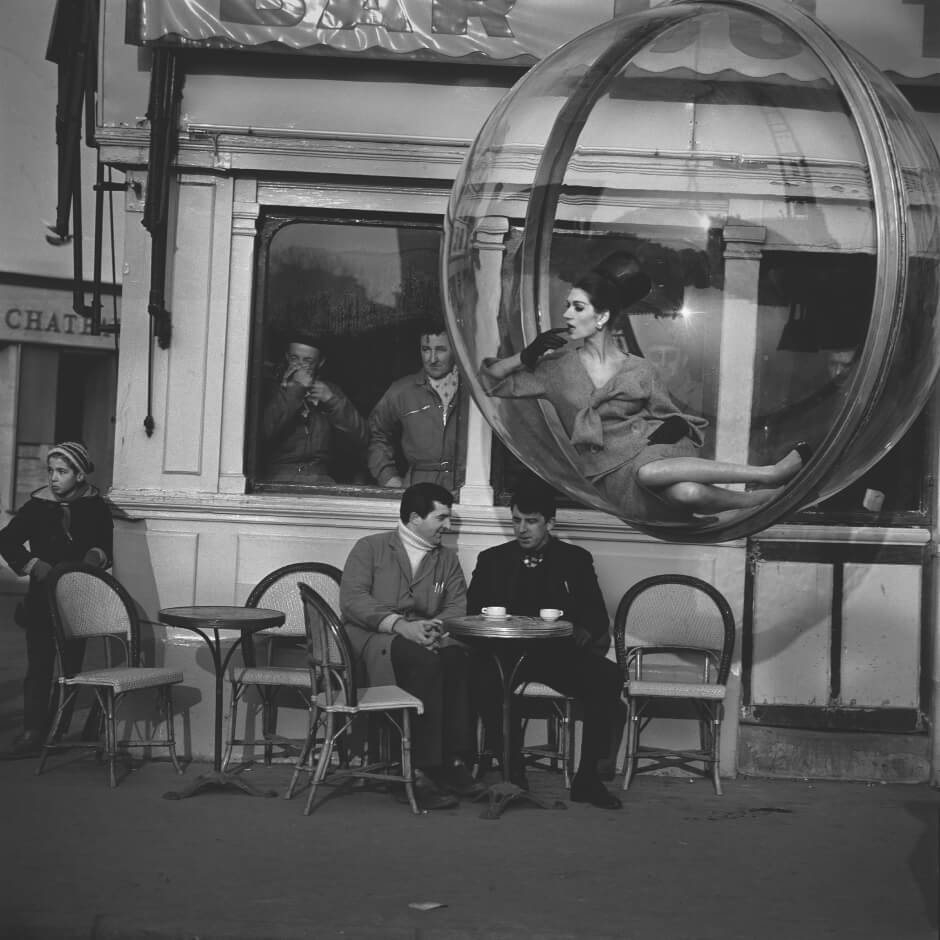

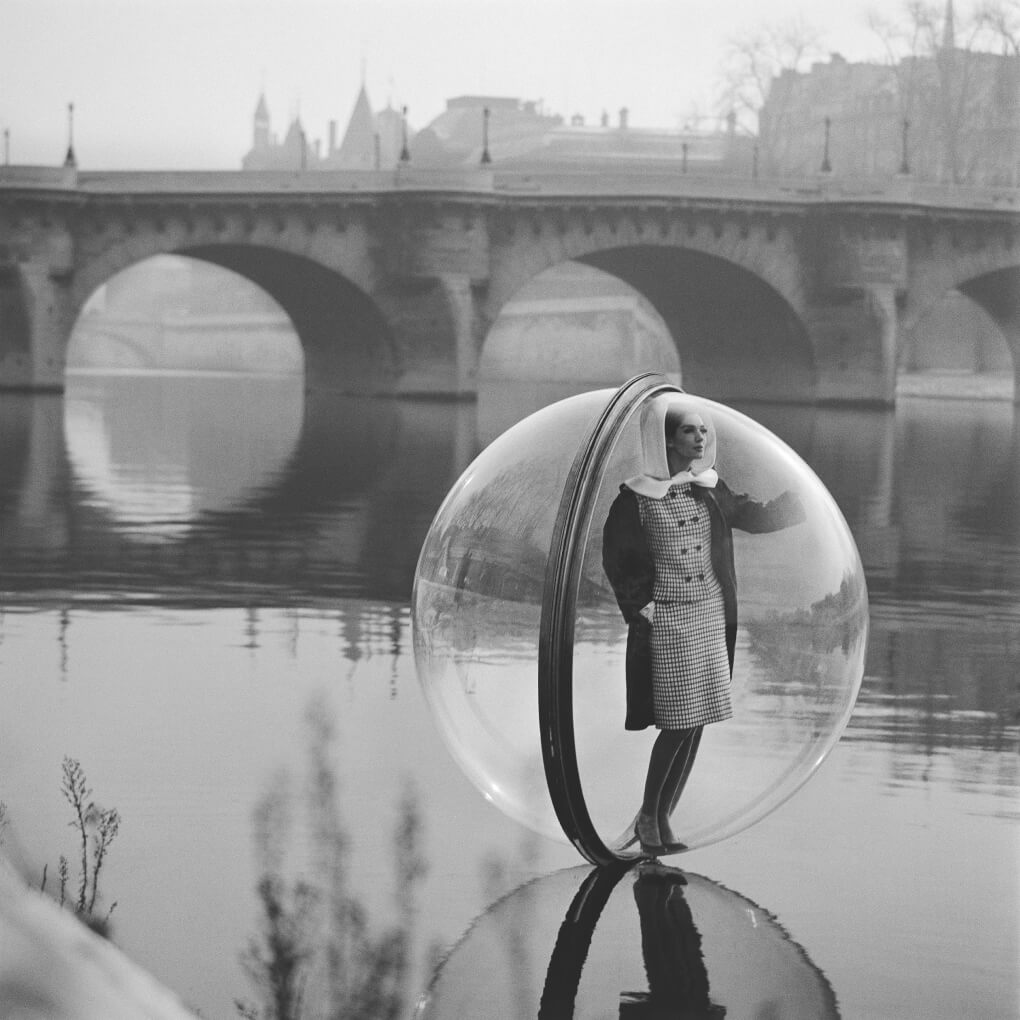

And it was that very image that inspired the work that put Sokolsky on the photography map with his iconic 1963 ‘Bubble Series’. At the age of 21, after years of taking pictures and taking them to agencies who all said they were “too artsy”, he was finally invited to join the photo staff of Harpers Bazaar by Henry Wolf, the magazine’s visionary art director. “I had been playing with cameras since I was a little boy and by the time I was shooting for Bazaar I had already been learning my ‘piano’ for 10 years.”

Although he was still learning on his feet, Sokolsky was rebellious by nature and would couple his street smarts with his deeply vivid imagination to challenge the aesthetic conventions of the editorial worlds. He was friendly but equally competitive with fellow star photographers of his day - Art Kane and Richard Avedon. This tension contributed greatly to what is now considered the golden age of the American magazine.

In December of 1962, Nancy White, the then editor of Harper’s Bazaar, called Sokolsky to inform him that he had been chosen to photograph the Spring Collections in Paris, the ultimate dream of most young fashion photographers. The news triggered an idea that had been hibernating in his mind for a long time, and recalled the Hieronymous Bosch painting from his memory.

SokoIsky knew he had struck gold. He was going to shoot the Collections in a transparent bubble. “But with the awareness that I was prone to live in my own head much of the time, and inclined to severe criticism, I began to have doubts as to whether I could create images on film that reflected the images in my mind’s eye,” he recalls. Complicating this creative process, were the whispered doubts that were already coming from some factions at Harper’s Bazaar. Once committed, there would be no turning back. “The reality at hand was, that if I faltered at the first location, if everything did not go like clockwork, I would be stuck with doing the entire collection in the studio.” The project at this point had become so controversial and intriguing, that adventure overtook reason and it was moving forward of its own volition.

“My assistant, Frank Finnochio, took the camera from my hands and pretended to photograph Simone in the Bubble. I was puzzled by his actions, and especially by the roll of film and the Hasselblad magazine that he covertly stuffed into my pocket as the police swarmed and began to arrest the crew. When I realised what was going on, I slipped into a cab as I watched the crew being hauled away in the French equivalent of a paddy wagon. Frank was also my printer, who spent many sleepless nights keeping up with the maddening, if not impossible schedule. His dry humour was the catalyst that kept the team going, whatever the circumstance. Hours later, after their release, the crew met in the lobby of the St Regis hotel, where I handed Frank two undeveloped rolls of film. He looked at me angrily and said, “I thought you would’ve developed the film by now, we’re never going to make the deadline!” Suddenly Frank broke into a broad smile and said, “Congratulations kid, this collection is now history.”

“To this day, I am still not sure if Serge and the Chief of Police did not show up at this last location intentionally, or as Serge explained at the wrap dinner, straight-faced, that he thought we were shooting at the Eiffel Tower!”

As he looks back on the shoot today, Sokolsky is somehow moved to tears, as if still in disbelief of his own triumph. “When you’re involved with consequences, where’s the time for your own personal space?. Everything today is so monitored and modulated. People are copying things. They haven’t been taught to discover who they really are. I was not cogniscent that I was doing anything special at the time. The simple act of doing and being who I am is what I did. Life is really the act of doing. When you’re doing it, there’s no sense of perspective until it actually manifests. Everything is about action and review.”

“You could never pull off a shoot like this today,” said Sokolsky in an interview in the Los Angeles Times in November 2007, of his ‘Bubble Series’ of photographs. “Insurance and permits alone would cost millions of dollars.”

The ‘Bubble Series’ and other wildly inspired fashion editorials subsequently caught the eye of many advertising creatives, and soon Sokolsky was shooting prolific campaigns across America. The Digital Journalist states that he was “the most successful advertising photographer of the 1960s”.

As most advertising work goes uncredited, Sokolsky became known primarily for his groundbreaking editorial work and celebrity portraiture. Drawing upon his fascination with Surrealist art (and encouraged to do so by a visit to do so to his studio from Salvador Dali), he was fearless in upending all notions of scale, proportion, visual rationality, and the laws of physics. Regardless of context, Sokolsky’s work always pops and provokes. “Really, I’m only interested in photography as a tool for exploring and visualizing psychological and emotional conditions.”

In the 1970s, Sokolsky expanded his visual repertoire to film and fittingly, he moved to Los Angeles. He became a prolific shooter of striking television commercials that bore all the innovation and glamour of his photographic work. He has continued to shoot fashion photography and other editorial assignments, and his work has moved towards an increasingly cinematic style. Sokolsky thinks in big questions that inspire a visceral visual narrative.

A young Ali MacGraw worked with Sokolsky at that time as his personal assistant, stylist and producer. They had met a few years earlier at Harper’s Bazaar where MacGraw had worked as Diana Vreeland’s assistant. “Ali was a gifted communicator who could translate ideas and make them readily accessible to art directors and editors,” remarks Sokolsky of MacGraw. “A typical creative meeting would unfold as follows. I would say, “I’m thinking of photographing the collections in a glass bubble. One of the images I see is, Simone in the bubble, coming through the early morning mist on the River Seine.” The silent gasps and guarded expressions of being in the presence of an ‘impractical eccentric’ quickly disappeared as a sea of drawings emerged from Ali’s hand almost as quickly as I could describe the images. The drawings were a great relief, as they were instant depictions of my ideas enhanced by Ali’s rendering of whimsical characters that readily seduced the viewer.”

Eli Pollock was Sokolsky’s studio chief and collaborator in the construction of devices that transformed his ideas into reality, and Pollock and his crew fabricated the Bubble in ten days. The hemispheres were made of Plexiglass, and the hinged rigs of aircraft aluminium, rendered from a design that Sokosky sketched on a brown paper bag. The Bubble went through a battery of rigging tests and then had its ‘maiden flight’ in his studio.

Simone d’Aillencourt, Sokolsky’s favourite model at the time, walked up to the Bubble which was suspended from one of the studio skylights, studied it, smiled, and remarked, “You’re going to hang it over the Eiffel Tower, yes?” Suppressing a grin, Sokolsky said, “Maybe.” D’Aillencourt climbed into the Bubble as if she was reliving an event from a past life. She explored the walls of the sphere, refining the body language that evolved in the continuing collaboration.

In early January, Sokolsky shot the cover for the March 1963 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. He photographed d’Aillencourt in the Bubble overhanging the cliffs of Wee Hawken, New Jersey, with the skyline of New York in the background. This was the test to see if the concept was feasible. The shoot went off without a hitch, and Sokolsky was touched when Marvin Israel, Ruth Ansell and Bea Feitler, the art department of Harper’s Bazaar, called to congratulate him.

On January 20th, 1963, Sokolsky and his team flew to Paris to photograph the Spring Collections.

A telescopic crane would drive up to a designated spot at the location, followed by a small van whose rear doors would open to reveal the Bubble nestled in its cradle. The crane operator then lowered the cable over the Bubble, so that Pollock could attach the finer aircraft cable to the grapple. D’Aillencourt was made-up and dressed in a camper parked a small distance away. The Bubble was suspended a few feet off the ground so that it could easily swing open for entry. D’Aillencourt then got into the Bubble, and Pollock would lower the hinged hemisphere, locking her safely within (there was, of course, a space between the hemispheres, so that she could breathe). The crane controller eagerly followed the hand signals of his partner, as the Bubble was raised into the final position. There were times when this choreographed dance turned into a Laurel and Hardy comedy.

Photographing in an around Paris was under the jurisdiction of the Beaux-Arts, which required three months prior notice in order to issue the necessary permits. It soon became highly apparent that photographing something as conspicuous as the Bubble without the proper papers would be a major, if not insurmountable task.

Upon hearing of this dilemma, Sokolsky’s friend Serge Marquand, a well-known character actor in France, appointed himself as the crew’s official liaison. Marquand cajoled his card playing partner, the Chief of Police, into bending all the rules in order to accommodate the shoot. “Carrying on like teenagers, they would show up at each location and keep the local police off our backs,” recalls Sokolsky. “I might add, that Serge was a madcap joker who would do anything for a laugh. On the morning of the last shoot, Serge and the Chief were nowhere to be found, and after exposing only one and a half rolls of film, we were suddenly surrounded by a convoy of police cars.”

“My assistant, Frank Finnochio, took the camera from my hands and pretended to photograph Simone in the Bubble. I was puzzled by his actions, and especially by the roll of film and the Hasselblad magazine that he covertly stuffed into my pocket as the police swarmed and began to arrest the crew. When I realised what was going on, I slipped into a cab as I watched the crew being hauled away in the French equivalent of a paddy wagon. Frank was also my printer, who spent many sleepless nights keeping up with the maddening, if not impossible schedule. His dry humour was the catalyst that kept the team going, whatever the circumstance. Hours later, after their release, the crew met in the lobby of the St Regis hotel, where I handed Frank two undeveloped rolls of film. He looked at me angrily and said, “I thought you would’ve developed the film by now, we’re never going to make the deadline!” Suddenly Frank broke into a broad smile and said, “Congratulations kid, this collection is now history.”

“To this day, I am still not sure if Serge and the Chief of Police did not show up at this last location intentionally, or as Serge explained at the wrap dinner, straight-faced, that he thought we were shooting at the Eiffel Tower!”

As he looks back on the shoot today, Sokolsky is somehow moved to tears, as if still in disbelief of his own triumph. “When you’re involved with consequences, where’s the time for your own personal space?. Everything today is so monitored and modulated. People are copying things. They haven’t been taught to discover who they really are. I was not cogniscent that I was doing anything special at the time. The simple act of doing and being who I am is what I did. Life is really the act of doing. When you’re doing it, there’s no sense of perspective until it actually manifests. Everything is about action and review.”

“You could never pull off a shoot like this today,” said Sokolsky in an interview in the Los Angeles Times in November 2007, of his ‘Bubble Series’ of photographs. “Insurance and permits alone would cost millions of dollars.”

The ‘Bubble Series’ and other wildly inspired fashion editorials subsequently caught the eye of many advertising creatives, and soon Sokolsky was shooting prolific campaigns across America. The Digital Journalist states that he was “the most successful advertising photographer of the 1960s”.

As most advertising work goes uncredited, Sokolsky became known primarily for his groundbreaking editorial work and celebrity portraiture. Drawing upon his fascination with Surrealist art (and encouraged to do so by a visit to do so to his studio from Salvador Dali), he was fearless in upending all notions of scale, proportion, visual rationality, and the laws of physics. Regardless of context, Sokolsky’s work always pops and provokes. “Really, I’m only interested in photography as a tool for exploring and visualizing psychological and emotional conditions.”

In the 1970s, Sokolsky expanded his visual repertoire to film and fittingly, he moved to Los Angeles. He became a prolific shooter of striking television commercials that bore all the innovation and glamour of his photographic work. He has continued to shoot fashion photography and other editorial assignments, and his work has moved towards an increasingly cinematic style. Sokolsky thinks in big questions that inspire a visceral visual narrative.

Our conversation moves into the present, the world of digital photography, Photoshop, and the future. “The digital world has made people step back,” he says with a slight hint of disdain. “Ideas are not digital. All that counts is content. Ideas are real.” And Photoshop? I have shown his Bubble images to several people prior to our interview and the question that has repeatedly arisen has been the obvious, “How did he do that without Photoshop?” Sokolsky’s response? “The first caveman that scratched a picture on the wall and then changed it slightly, that was the beginning of Photoshop!”

It is about 18 months since I first met Melvin Sokolsky at The Peninsula in Beverly Hills and I was both surprised and delighted to receive an email from him in March announcing the release of his new book - the weighty 472-page, 22-pound, ‘Archive’, a retrospective monograph of his images from the 1960s to the present.

Back in October 2007 he had mentioned how unhappy he was with his previous book ‘Seeing Fashion’, first published in 2000. It appeared from the preview of ‘Archive’ that he sent me that he has more than compensated for that disappointment. My first question to Sokolsky is what makes ‘Archive’ what it is and how does it differ from ‘Seeing Fashion’? “Other than the simple fact that I was in control of the printing, design, and the sequencing? In simple terms, ‘Archive’ is a visual and spiritual portrait of me at this time in my life. As I turned the pages and reviewed the sequence of images for the book, many memories streamed through my mind. Each image takes me back in time to the places and the people I have shared my life with. The cumulative effect of this reverie clearly reveals that my photographs are the spiritual and visual archive of my life.”

Melvin Sokolsky’s photographs are deeply imaginative and challenge the aesthetic conventions of the advertising and editorial worlds. Reflecting his fascination of Surrealist art, Sokolsky’s photographs explore and play with spatial relationships, scale, proportion, visual rationality and the laws of physics. By using oversized furniture, upside down rooms and dreamscape worlds, Sokolsky defines an aesthetic that continually creates images that transcend the clothes they purport to feature.

The editing process involved in the creation of ‘Archive’, when one views the images contained within and are aware of the massive body of work that Sokolsky has produced over more than five decades, must have been arduous, not to mention at times emotional for the photographer. “My first thoughts were to sequence what I believed were my best pictures. A few days into the process I realised that best pictures were only opinions,” he remarks. “When a musician plays a false note, or a singer sings off key, the audience will react in concert to the painful sound. It soon became obvious that in order to reveal my inner clock, all of my images should be explored. The images that make up one’s life of work are the sum total of the being. The book has now been printed and I still get a pang of remorse that I have left out many important images.”

That being said, ‘Archive’ does seem to comprise Sokolsky’s best work and some very significant shoots in his career. Other than his famous and previously mentioned ‘Bubble’ images, the book documents other seminal photographic milestones including his ‘Fly’ series shot in Paris in 1965 which depicts models in haute couture gowns flying high above the city’s rooftops; his portraits of such photogenic characters as Mia Farrow, Julie Christie, Candice Bergen, Ben Affleck and Slash from Guns ‘N‘ Roses, amongst others; his iconic Twiggy images (currently also included in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition ‘The Model As A Muse’); photographs that toy with the concept of light and others that comment on various worlds, and more. It’s a visual assault that clearly conveys Sokolsky’s acute awareness of the spatial relationships between people and the objects that surround them. “As far back as I can remember, I would impulsively change my point of view in order to find a position that was more pleasing to my eye,” he notes.

For the first time, upon reading the introductory pages of ‘Archive’, I discover more about the most important person in Sokolsky’s life. At age 20, having rented his first studio, the young Sokolsky met a beautiful, young British model by the name of Beryl Button Whelan. “She was having her test shots taken by my friend Peter Oliver, who was the assistant of William Helburn, a photographer of note at the time,” writes Sokolsky in his introduction to ‘Archive’. “After the shoot, Button and I went for coffee. It was after the second cup of coffee and the walk across Central Park that I realised I had met someone with whom I had a rapport I had never experienced before. My purpose isn’t to tell you my love story but to explain how affinities can stimulate self-discovery, which I believe translates into personal vision.”

It was in his modest studio on East 39th Street in New York that Sokolsky’s lifelong romance with Button began. She quit her job as a fur model at Bergdorf Goodman and became his life partner. “The result was like magic,” says Sokolsky. “For the first time, the images of my mind’s eye were now being translated into images on film. Button had a deft touch in the facilitation of my pictures. If I rejected a prop, she intuited why, so there were no hurt feelings.

This stunning young woman with a pleasant English accent was also apparently the perfect intermediary with clients, which knowing Sokolsky, was unlikely his forte. “It was amusing to watch how well she could manage any distractions that were headed my way.”

Within a few years, Sokolsky had bought an old five-storey tenement which he renovated into a studio that was capable of creating every element that went into the making of his photographs. The quality of his work attracted a team of assistants and stylists that has

Dummy content to demo read more